Valery Dunaevsky | I ‘Oppenheimer’ (Draft to the commentary about the film)

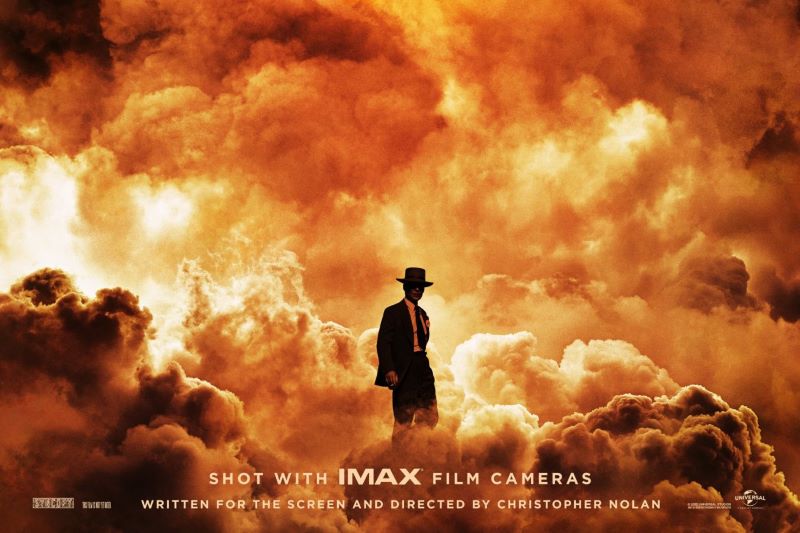

I am not a professional film critic, so I will refrain from categorical assessments of the film Oppenheimer (2023), such as weak or strong. At the same time, despite some ambiguities in the content of recreated conversations and the identification of characters, I was impressed when I watched the film—a dizzying kaleidoscope of events, scenes, and faces that brought me personally back to the 1950s, the years of my youth and formation. The action-packed film captures a tense period when the potential of a nuclear holocaust was fanned on both sides by propaganda machines and when there was still another side with which to discuss the topic.

Оставайтесь в курсе последних событий! Подписывайтесь на наш канал в Telegram.

I don’t know if most viewers would share any of my points of view about any particular weakness in the script. Still, at an evening session that I attended with my wife (having purchased senior citizen tickets for $7 each), the hall was packed. During the entire more than three hours of viewing, no one wanted to leave for a minute out of necessity. Whether it was because the audience, myself included, was so engrossed in the movie, or they didn’t know (or had forgotten) Hitchcock’s rule about how the length of a movie should be directly related to the strength of the human bladder, or, finally, they because didn’t want to miss out on possible additional erotic moments, considering that the first and, as it turned out, only erotic scene was fairly early in the film. (Director’s find?)

One way or another—six of one, half dozen of the other, as we say in the Midwest—the film was a box office hit. Thus, for its creators, any perceived script weaknesses did not translate into a financial setback, providing a basis to believe that any weakness was relative. In this regard, I think it would not be out of place to translate and paraphrase Sergei Dovlatov’si satirical couplets for this situation, replacing “poets” with “storytellers”:

Storytellers—even if they are bad—

Are still needed like light.

A script is always a product of an era,

And without products, there is no life.

Although the rhymes of the couplet in Russian have somewhat lost their luster in translation, the original pun can still be savored: in the original Russian, the word for products also means food. Of course, in modern life, all products are made to be consumed.There have been previous films on this topic, such as the epic drama Fat Man and Little Boy (1989) and the documentary The Bomb (2016), which I have not seen. Oppenheimer (2023) focuses on the psychological drama of its protagonist, physicist Robert Oppenheimer, who lost the opportunity to continue his activities after his contributions to the creation of atomic weapons, which helped lead to the early surrender of Japan in World War II and the introduction of the world to the Nuclear Age. The film’s sound, lighting, and other cinematic elements helped reflect the intensity of Oppenheimer’s fraught relationships with fellow scientist Edward Teller and influential Atomic Energy Commissioner Lewis Strauss, which contributed to Oppenheimer’s loss of a security clearance. Among the reasons for this debacle during the McCarthy years, highlighted by his congressional hearings on anti-American activities, were Oppenheimer’s early pro-communist sympathies and his resistance to the development of a more potent thermonuclear bomb, as proposed by Teller. The film also reflects the drama of Strauss, who was hit by karma in the late 1950s, as he was prevented from an anticipated significant rise in his career due in part to his past opposition to Oppenheimer.

Being somewhat familiar with the events described in the film and the names and images of the creators of the atomic weapons that had been planted in my head from a young age, I was intellectually pleased by identifying my mental images with the convincing versions presented on the screen. For example, Teller was Teller, General Groves was Groves, and Einstein was a sweet old Einstein. Also, one of the leading atomic developers, who also contributed to the prevention of American nuclear hegemony, was the easily recognizable theoretical physicist and student of Max Born, the German communist Klaus Fuchs. The Rosenbergs weren’t the only spies trying to level the playing field.

The novelty I found in watching the film was the realization of the incredible fact, for me as an engineer, that the version of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima had not been previously tested. It was a cylindrical, uranium-235 gun-type bomb named Little Boy, with a yield of 15 kilotons of TNT. In this bomb, a hollow uranium cylinder was fired at a cone of the same uranium to create a supercritical mass during the powerful impact connection of the components, and a nuclear chain reaction would then occur. Except for testing its individual elements, the bomb did not pass any detonation tests. The famous Trinity test on July 16, 1945, at the Alamogordo Bombing Range in the desert 210 miles south of Los Alamos, New Mexico, was carried out on a sample of the Gadget plutonium bomb (19 kilotons). The explosion flash was visible for more than 150 miles, the shock wave spread for more than 40 miles, and a radioactive cloud rolled all the way to Indianapolis, illuminating some of the photographic films being made there at an Eastman Kodak factory.

The final version of the plutonium bomb, Fat Man (not much different from Gadget), was dropped on Nagasaki. While watching the movie, I noticed the elliptical shape of the bomb mounted on the test tower and assumed that Gadget and Little Boy were not the same. The developers apparently thought (which in fact seems to be what occurred) that a gun-type bomb, which is a more straightforward design than a plutonium bomb, would be fine. Hey, Robert! Ah yes, Oppenheimer and his team! Although I had seen images of these bombs previously and naturally read about the processes in their operation, the information provided about testing somehow did not register with me. But the moving image (even the Hollywood version) helped, confirming the well-known thesis, “Of all the arts, the most important for us….”

The preference given to the plutonium bomb is explained by the complexity of the enrichment process of uranium 235 (U-235) to obtain a sufficient amount of the corresponding refinement. In contrast, a relatively effective method was found to obtain the fissile plutonium isotope PU-239 from the uranium isotope U-238, about which, I remember, Arkady Raikin2 taught:

Fall asleep, my Robert.

We’ll wake early with the dawn.

And your mom will tell us,

If it’s not too late,

About the nucleus

Of uranium 238.

(Look, in the Soviet Union, even a stage worker could quickly slapdash an atomic bomb. So, why do evil tongues talk about a few spies?)

At the same time, plutonium was not suitable for a gun-type bomb. As it had a faster decay rate than U-235, it could cause premature fission (i.e., fission before the formation of a critical mass), thus preventing a full-fledged chain reaction. The plutonium bomb required an entirely new approach. The scope of the film suggested to me the need to restore knowledge on this topic. For example, within some circles, there has been recent clarification that a decisive breakthrough in the creation of the plutonium bomb was the work of a Harvard professor of chemistry of Ukrainian origin, Georgy Kistiakovsky, who was involved in the Manhattan Project as head of the Department of Explosives at Los Alamos, and later became a scientific adviser to President Eisenhower.Thus, one cannot fault (in the magnificent but gory outcome of the nuclear bomb’s creation) only Elsa Lowenthal’s husband (her cousin), the eccentric professor Albert Einstein, who did not directly participate in the project but, together with fellow physicist Leo Szilard, pushed Washington to create it. Kistyakovsky and his colleagues solved a critical problem in the creation of a plutonium bomb (which, unlike a uranium bomb, works on the principle of implosion in that a plutonium core is compressed to a supercritical mass under high pressure): the creation of appropriate charges that, covering the core, would quickly and directionally compress it with a shock wave during detonation.

Looking through the comments on the film in a rave review in The New York Times, I noted what some of them see as a flaw in it, as well as in the book on which it was based, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin: the lack of an adequate assessment of the significance of the atomic bombing of Japan on its unconditional surrender. I am unsure if the film’s lack of emphasis on this aspect detracts from its importance per se. Still, I want to point out that this apparent omission leaves the impression that the atomic attack on Japan was the only factor contributing to its early surrender.

However, in recent years, there has been enough literature showing that only the shock from various retributions that manifested themselves almost simultaneously—the American nuclear strikes and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan, followed by the Red Army’s invasion of Manchuria and South Sakhalin, as well as the continued flattening of Japan with non-nuclear ammunition by B-29 bombers flying out of the Mariana Islands—rather quickly forced the leadership of Japan to an unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945, which happened, however, after they overcame an internal attempt by a group of officers to resist this action.

The continuation of Lend-Lease deliveries to the Soviet Union, which included thousands of vehicles, tanks, and aircraft until September 20 (although September 2 was the day Japan signed the official surrender documents aboard the U.S.S. Missouri) made it much easier for the Soviets to defeat the Japanese forces.An example of evidence of the importance to Washington of Moscow’s actions against Japan to defeat it as soon as possible can be seen in an American postal cover from 1945 (https://kontinentusa.com/val-dunaevsky-what-did-really-crush-japan-the-a-bombs-or-a-soviet-invasion-in-manchuria/), the text of which enthusiastically announces, “August 8, Japan’s worst fears came true. Russia has declared war on Japan.” It is obvious that the cover was released after Hiroshima (August 6) and probably before the attack on Nagasaki, since Molotov made the war’s declaration to the Japanese ambassador in Moscow at 11 pm on August 8, Trans-Baikal time (12 hours before the strike). [As a philatelist, about 30 years ago, I purchased the original described envelope.]

Returning to the film, while some viewers point to the script’s shortcomings, voices are growing in the blogosphere that condemn the movie based on its supposed lack of political correctness. Some complain that the picture does not reflect the suffering of the locals, mainly Native Americans and Hispanics, who lived in small numbers on the leeward side of the Trinity test site (in the American press, they have been identified as the “downwind” people), were exposed to a significant dose of radiation with corresponding unfavorable outcomes, and allegedly have not received sufficient compensation from the government. This topic is clear and broad. However, even a newspaper as liberal as The Los Angeles Times, which provided an upbeat assessment of the film, believes that the lack of direct coverage of the unfortunate events associated with the testing of nuclear weapons in America and the demonstration of mass casualties of the atomic bombings in Japan was the result of restraint and not an intentional erasure of these phenomena from memory. At the same time, the newspaper believes that the film successfully demonstrates Oppenheimer’s mental anguish in connection with the results of his activities. However, more radical voices altogether denigrate the movie for the reasons described above, and even for a more serious, in their opinion, reason that the film shows only white people and not a single colored one. I’m afraid I have to disagree with the latter view. In a number of scenes, several non-white characters were represented.

Given that this essay had to raise some pretty serious questions, some of which I don’t have answers to yet, I’m going to end it on a light note by posing for the readers a few trivia questions related to the film to ponder:1. Did Einstein wear socks in winter while walking with Gödel in Princeton near the Institute for Advanced Study? It is known that he did not like to wear socks, and he did not wear them even during his citizenship processing with the US government.

2. How much did the spy Klaus Fuchs pay for his used Buick in Los Alamos in 1944?

3. In the erotic scene, Oppenheimer is not depicted in a “missionary” position. I wonder if the film was attempting to provide a brief suggestion of a particular assessment of his personality.

In conclusion, I want to note that in my memoirs—V. Dunaevsky, A Daughter of the “Enemy of the People,” Xlibris, 2015, p. 95—there is unique information about the Soviet–Japanese War of 1945, which I have recalled from the stories of family friends, who were participants and witnesses to that event. The book is available through Xlibris and Amazon. Amazon also offers a very inexpensive e-book version.

P.S.

Even if they are bad,

We need our historical films,

As grease for our cultural wheels.

Because without lubrication,

Even the best wheel

Will squeal in protest while moving forward.

i1 Sergey Dovlatov (1941–1990) was a renowned Russian–American writer

2 Arkady Raikin (1911–1987) was a famous Soviet stand-up comedian, theater and film actor, and stage director.

Val.

Copyright © 2023 by Valery Victorovich Dunaevsky

Valery (Val) Dunaevsky

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий