Val Dunaevsky | What did really crush Japan? The A-Bombs or a Soviet Invasion in Manchuria?

Several lesser-known documents of WWII suggest the critical role that a Soviet invasion in Manchuria in August of 1945 played in the speedy capitulation of Japan. This opinion is contrasted with the one advanced in COUNTDOWN 1945 by Chris Wallace.

“It’s very clear that Hiroshima alone did not budge the Big Six, the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War, toward surrender. Not one iota. They accepted the news with a shrug. Nagasaki, however, in conjunction with the Soviet declaration, was decisive.”

Todd DePastino

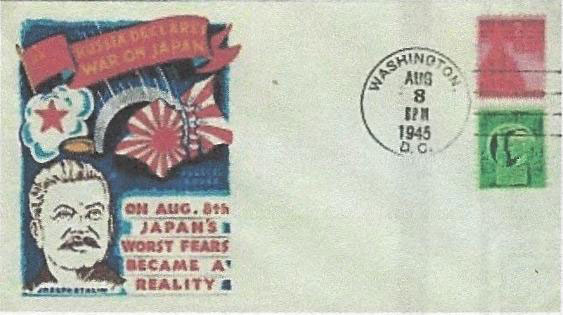

The illustration above bearing the image of WWII Soviet leader Joseph Stalin is a patriotic U.S. postal cover of August 1945 commemorating the USSR joining the U.S. in the war against Japan and was postmarked on the day when it happened. The celebratory wording states, “RUSSIA DECLARES WAR ON JAPAN. ON AUG. 8TH, JAPAN’S WORST FEARS BECAME A REALITY.”

The demonstration of this artifact is not for the glorification of the dictator—in fact, this author’s grandfather perished in one of Stalin’s Gulag camps—and not for justification of all the actions of the USSR in the Far East in the waning days of WWII. This is just to keep in touch with history when discussing the relevant events and avoid sliding into the cancel culture swamp of modernity.

The message on this rare philatelist item that was obviously issued after the Hiroshima bombing on June 6, 1945, implies that even after the first U.S. nuclear attack on Japan, some segments of the American public believed that the entrance into the war by the Soviet Union was going to be Japan’s worst nightmare.

The declaration of war took place on August 8 almost at midnight in the Far East, and the Russian invasion in Manchuria started promptly after midnight, three days after Hiroshima and on the same day as the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. One week after the invasion and following a speedy defeat of the Kwantung Army in Manchuria, Japan surrendered. The aforementioned public sentiment is not echoed in the recent book by TV Journalist Chris Wallace and investigative journalist Mitch Weiss, Countdown 1945: The Extraordinary Story of the Atomic Bomb and the 116 days That Changed the World, published by Simon & Schuster in June of this year. The book has a number of other omissions and errors, which are addressed in this article along with its main topic, a discussion on the relative significance of both the A-bombs and Russia’s entrance in the Japanese war on the decision of Japan to capitulate.

The interest of the author, who was born in the middle years of WWII, in the war events in the Far East and the capitulation of Japan is apparently rooted in his childhood memories of the stories told by relatives and friends of the family who participated in the short but fierce and bloody (for both sides) Russo-Japanese war in 1945. The Japanese losses were, however, ten times those of the Russians. The Russian military campaign against Japan started exactly three months after the surrender of Germany, just as Stalin had promised to Roosevelt at the Yalta Conference in February of 1945.A family friend who participated in the campaign told about the difficulties of defeating the well-entrenched enemy. Some of the most difficult to destroy fortifications included concrete pillboxes attached to the top of thin vertical steel poles. Such locations made these bunkers almost invisible through the canopy of the forest as the steel poles were almost indistinguishable among the trees. All of which made it that much more difficult for the Russian artillery to stop the fire that rained down from the elevated machine gun nests.

Suppressing these fortifications (where it was later learned, the Japanese gunners had been chained to their weapons) finally proceeded due to the direct action of the infantry. However, it resulted in large losses among the Russian fighting men.

The author remembers also the personal trophies that his uncle, a medical doctor, Yuri Osherovsky, brought back from the war. These included a miniature movie-camera and an amazing winter coat that could be taken apart piece by piece to the point that only a portion of the coat in the form of a vest would have remained to be worn.

After the rout of the Imperial Kwantung Army, which had occupied Manchuria since invading in 1931, the Soviet Army discovered secret installations for experimenting with and producing chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction. At these locations, the Kwantung Army was also responsible for some of the most infamous Japanese war crimes, including the operation of several human experimentation programs using live Chinese, American, and Russian civilians and POWs. The decimation of the Kwantung Army and seizure of Manchuria with its oil refineries and powerful industries substantially crippled the Japanese economy and its prospects for successful long-term military actions.

What did drive Japan’s decision to surrender, the atomic bombs or the Soviet invasion, or both? The author’s interest in this historically important question, which is still debated, rose one day in the 1990s when he as a philatelist came upon and bought the postal cover illustrated in this article. In turn, when Countdown 1945 arrived at bookstores several weeks ago, the author acquired a copy of the book at a local Barnes & Noble outlet, saving on the way 10% of the cover price through his membership discount, and expecting that the book would bring some clarity to the mind-boggling question of Japan’s decision to capitulate—the clarity that he did not find before in perusing tons of relevant information. However, the conundrum of the Japan surrender decision continues.

For example, a Japanese author, Sadao Asda [1] considers that the atomic bombs rather than the Soviet entry into the war had a more decisive effect on Japan’s decision to surrender.

In turn, another Japanese historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, a professor of modern Russian and Soviet history from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in his essay in The Asia-Pacific Journal [2], argued that the entry of the Soviet Union into the war against Japan played a much greater role than the atomic bombs in inducing Japan to surrender because it dashed any hope that Japan could terminate the war through Moscow mediation:

“The Hiroshima bomb, although it heightened the sense of urgency to seek the termination of the war did not prompt the Japanese government to take any immediate action that repudiated the previous policy of seeking Moscow’s mediation. Contrary to the contention advanced by Asda […..], there is no evidence to show that the Hiroshima bomb led either Togo [Japan’s Foreign Minister Togo Shigenori] or the emperor to accept the Potsdam terms. On the contrary, Togo’s urgent telegram to Sato [Japan’s ambassador to the USSR] on August 7 indicates that despite the Hiroshima bomb, they continued to stay the previous course. The effect of the Nagasaki bomb was negligible. It did not change the political alignment one way or the other. Even [….] fantastic suggestion that the United States had more than 100 atomic bombs and planned to bomb Tokyo next did not change the opinions of either the peace party or the war party at all.Rather, what decisively changed the views of the Japanese ruling elite was the Soviet entry into the war. It catapulted the Japanese government into taking immediate action. For the first time, it forced the government squarely to confront the issue of whether it should accept the Potsdam terms. In the tortuous discussions from August 9 through August 14, the peace party, motivated by a profound sense of betrayal, fear of Soviet influence on occupation policy, and above all by a desperate desire to preserve the imperial house finally staged a conspiracy to impose the “emperor’s sacred decision” and accept the Potsdam terms, believing that under the circumstances surrendering to the United States would best assure the preservation of the imperial house and save the emperor.

This is, of course, not to deny completely the effect of the atomic bomb on Japan’s policymakers. It certainly injected a sense of urgency in finding an acceptable end to the war. Kido [a personal adviser to the Emperor] stated that while the peace party and the war party had previously been equally balanced in the scale, the atomic bomb helped to tip the balance in favor of the peace party. It would be more accurate to say that the Soviet entry into the war, adding to that tipped scale, then completely toppled the scale itself.”

In favor of this point of view testifies the surrender rescript of August 17 of Emperor Hirohito to his Japanese troops, in which the entrance of the Soviet Union in the war against Japan was presented as the sole reason to cease the hostilities [3]. The text of this rescript (if it is authentic) could, however, be interpreted as a way for the Emperor to nudge the hotheads of the military brass to accept the inevitable, which presented in the form of the Soviet invasion was possibly more palatable to the officers than bombs, even very powerful ones. This rescript differs from the one that Hirohito read on the radio to the nation on August 15 and in which he claimed the new super powerful bombs were the main reason to surrender. The surrender was signed on September 2, 1945. The Soviet Union continued to fight until early September.

In Countdown 1945, the discussion of the effect of the Russian invasion in Manchuria on Japan’s surrender is not very extensive. Meanwhile, a few lines throughout the book allude to the notion that Truman, having doubts that the atomic bomb would work, wanted a firm commitment from Stalin that the Russians would join the fight to ensure victory, regardless of the possible long-term consequences. On July 17, at the Potsdam Conference in a conversation with Truman, Stalin confirmed the promise he made at Yalta—to declare war on Japan by mid-August. Still, Truman and Churchill hoped that the bomb would make Stalin’s promises of entering the war with Japan irrelevant.

The invasion itself is covered in two short paragraphs on pages 239 and 254. On page 239, “The following day, August 8, The Soviet Union declared war on Japan. Soviet infantry [,] tanks and aircraft invaded Manchuria. Skeptics called the timing ‘convenient,’ and suspected the Soviets were more interested in expanding their empire to the Far East than defeating Japan.” On page 254, “Some historians argue Japan would have surrendered in 1945—without the United States either dropping the bomb or invading the homeland. Russia declared war on Japan on August 8, sending one million Soviet troops into Japanese-occupied Manchuria.” Following a passage about the Soviet attack on page 239, there are a couple of lines about the leaflets dropped from U.S. planes with the warning of a second nuclear attack. However, not mentioned in the book was that the B-29s flying from the Mariana Islands continued the intermittent strategic firebombing of Japan [4] through August 15, the day that Japanese Emperor Hirohito delivered his unconditional surrender rescript. In fact, on the fourteenth, 1,014 bombers hit the Japanese mainland, the largest raid ever in the Pacific theatre.The book is lacking in other significant details. One of the most glaring omissions is the reference to only a single spy inside the Manhattan Project: per page 164, “The Soviets had been conducting their own research for three years. And they had a spy inside the Manhattan Project. A German-born physicist at Los Alamos named Klaus Fuchs had supplied Moscow with valuable information.” Wow! I think one does not need to be a junkie of spy fact and fiction to understand that the above is quite an understatement of the level of Soviet penetration into the project [5]. A concern about the consequences of the American monopoly on atomic weapons after the war was, apparently, one of the leading factors in sharing the atomic information with Russians by several workers inside the Manhattan Project.

Along with the various omissions, which could be justified, at least partly, by the relatively small volume of the book, it exhibits a relatively large array of factual errors and lapses. For example, per page 108, J. Robert Oppenheimer, along with many others fled European fascism. However, Oppenheimer, in fact, was born in New York City. Although he studied in Europe for some time, he returned (unforced) to America in the 1920s. On page 50, the authors wrote that after the D-Day landing, “…Allied troops stormed west to Berlin.” One of Amazon’s reviewers of the book noted correctly that “If they did, they would have stormed into the Atlantic Ocean.”

Further, per page 173, a B-29 bomber flying from Hamilton Air Force Base in California brought to the island of Tinian the uranium projectile, a so-called “bullet,” that would be shot into the larger uranium cylinder and trigger the explosion of Little Boy (the gun-type atomic bomb that was detonated over Hiroshima). Meanwhile, per modern sources, particularly [6], the above information about the schematics of the bomb’s operation and the means of transporting the bomb components to the island is not quite correct. It was actually the projectile, representing a cylinder with a four-inch hole through the middle that was larger than the target, which was a solid spike measuring seven inches long with a diameter of four inches. The weight distribution of U-235 between the projectile and the target was approximately 60% to 40%. As mentioned in [7], “The actual Little Boy bomb was not a small projectile being shot into the larger target. It’s a large projectile being shot [onto] a smaller target. That is Little Boy was in fact a ‘girl.’”

Also, per [8], the Little Boy units, accompanied by the projectile, were delivered to Tinian on July 26 by the cruiser Indianapolis. In turn, the target assembly, divided into three parts, was brought to the island on July 28 aboard three Douglas C-54 Skymaster transport planes flying from Kirtland Army Airfield in Albuquerque, NM.

Four days after having finished its part of the secret mission (delivering the components for Little Boy) and then steaming to the Philippines, the Indianapolis was torpedoed and sank to the bottom of the Pacific with the loss of almost 900 men of the 1,200 sailors on board (p. 173). The men died during the sinking, or from exposure, dehydration, and shark attacks. This was the largest loss of life in history from any U.S. Navy ship sunk at sea.

After learning many years ago about their cruel fate that followed the cruiser’s, the author kept wondering about what course of events would have led to Japanese capitulation had the Indianapolis been torpedoed before delivering its deadly cargo to the island. Perhaps, they would not have been much different. Besides an implosion-type plutonium bomb, Fat Man, which was expended in a test, another plutonium bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, and yet another one was transported to Tinian in mid-August.

With regard to the book at hand, a couple of inaccuracies from those found in the section of Key Events are highlighted in the table below.| As given in the book | Clarification |

| 1932 – Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity is proven when British scientists John Crockcroft and E.T.S. Walton successfully split the atom. | A connection to Einstein is misleading. Splitting of the atom has nothing to do with the proving of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The first putative proof of the theory came in 1919 with British astronomer A. Eddington’s photographs of a total solar eclipse. |

| September 1, 1939 – World War II begins when Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland. | A more circumspect statement would have been justified. Many prior acts could have been considered as part of the war. It is known that WWII is conveniently marked as beginning with Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, and with Great Britain and France declaring war on Germany on September 3. However, the Soviet invasion took place on September 17. The book’s statement may serve only as a figure of speech, albeit an inaccurately worded one. |

Despite a multitude of inaccuracies and omissions, Countdown 1945 is, nevertheless, a brisk and riveting rehash of the extraordinary and fascinating events leading to the nuclear bombing of Japan and its surrender. The authors could be commended for their keen insight into the human factor that permeated all the events.

Anyhow, it is probably prudent to assume that not all the mysteries of the Manhattan Project have been resolved, and the jury is still out over the issue of which more affected Japan’s decision to surrender, the Russian invasion or the A-bombs.

As for the illustration at the top of the article, it was the last American cover showing Stalin in positive light. After the end of the war, it did not take long for Americans to realize that the relatively brief period of collaboration was over. One of the first confrontations widely publicized in American media centered on the fate of the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria. Following a secret decree by Stalin and in violation of Yalta agreements, more than 500,000 Japanese soldiers who laid down their arms were sent to the GULAG for hard labor. Stalin did not admit this fact until 1947, despite several inquiries by the Allies, [9].

[1] “The Shock of the Atomic Bomb and Japan’s Decision to Surrender—A Reconstruction,” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 67, no. 4 (1998).

[2] https://apjjf.org/-Tsuyoshi-Hasegawa/2501/article.html

[3] http://www.taiwandocuments.org/surrender07.htm

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LM5ShdGjwwQ

[7] http://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/2011/11/08/the-mysterious-design-of-little-boy/

[8] http://www.ww2f.com/threads/transporting-atomic-bombs.42353/

[9] https://carlbeckpapers.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/cbp/issue/view/168

Val Dunaevsky, U.S. citizen, Ph.D., MSME, is a reviewer for several international technical magazines and the author of the biographical/autobiographical memoir A Daughter of the ‘Enemy of the People’ (Xlibris, 2018) about life in the USSR in the middle of the last century.valvic833@gmail.com

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий